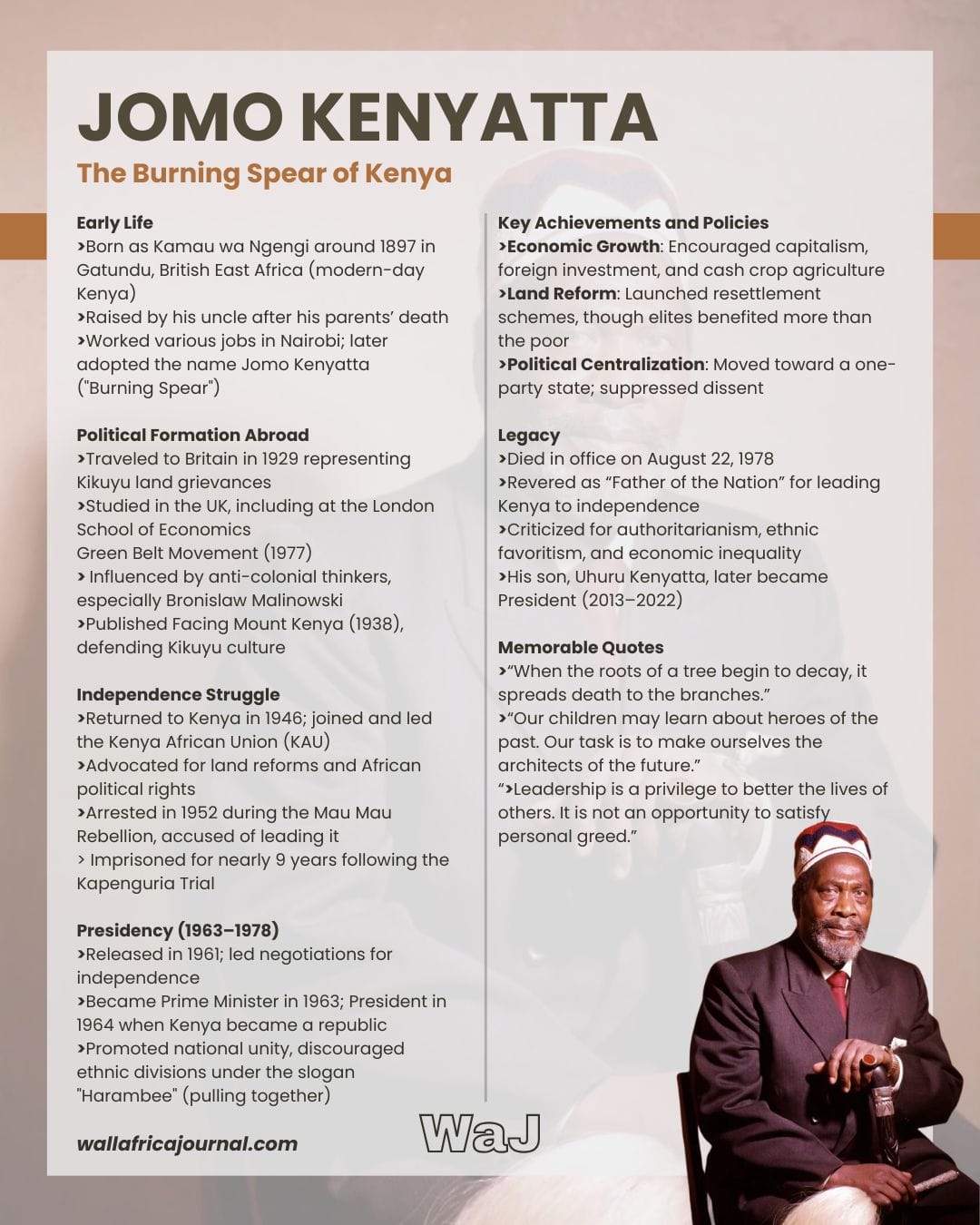

Jomo Kenyatta, born around 1897 in British East Africa, rose from humble beginnings to become the founding father of independent Kenya. Early exposure to colonial structures and missionary influence shaped his worldview. He joined the Kikuyu Central Association in the 1920s, advocating for land rights, and later traveled to Britain where he studied, engaged with anti-colonial thinkers, and published Facing Mount Kenya (1938), defending African traditions.

After returning to Kenya in 1946, Kenyatta led the Kenya African Union (KAU) and became a key figure in the nationalist movement. Though denied involvement, he was imprisoned during the Mau Mau Uprising. Upon his release in 1961, he led Kenya to independence and became its first Prime Minister in 1963 and President in 1964.

As leader, Kenyatta emphasized national unity through the “Harambee” philosophy, promoted economic growth, and initiated land redistribution—though often favoring elites. His presidency became increasingly centralized and authoritarian, marked by political suppression and ethnic favoritism.

Kenyatta died in 1978, leaving a mixed legacy: celebrated as the architect of modern Kenya, but also criticized for fostering inequality and authoritarianism.