Malawi is preparing for a pivotal presidential election that analysts say could mirror the anti-incumbent trend that swept across Africa in 2024, when voters in countries such as Senegal, Ghana, and Botswana unseated long-standing governments.

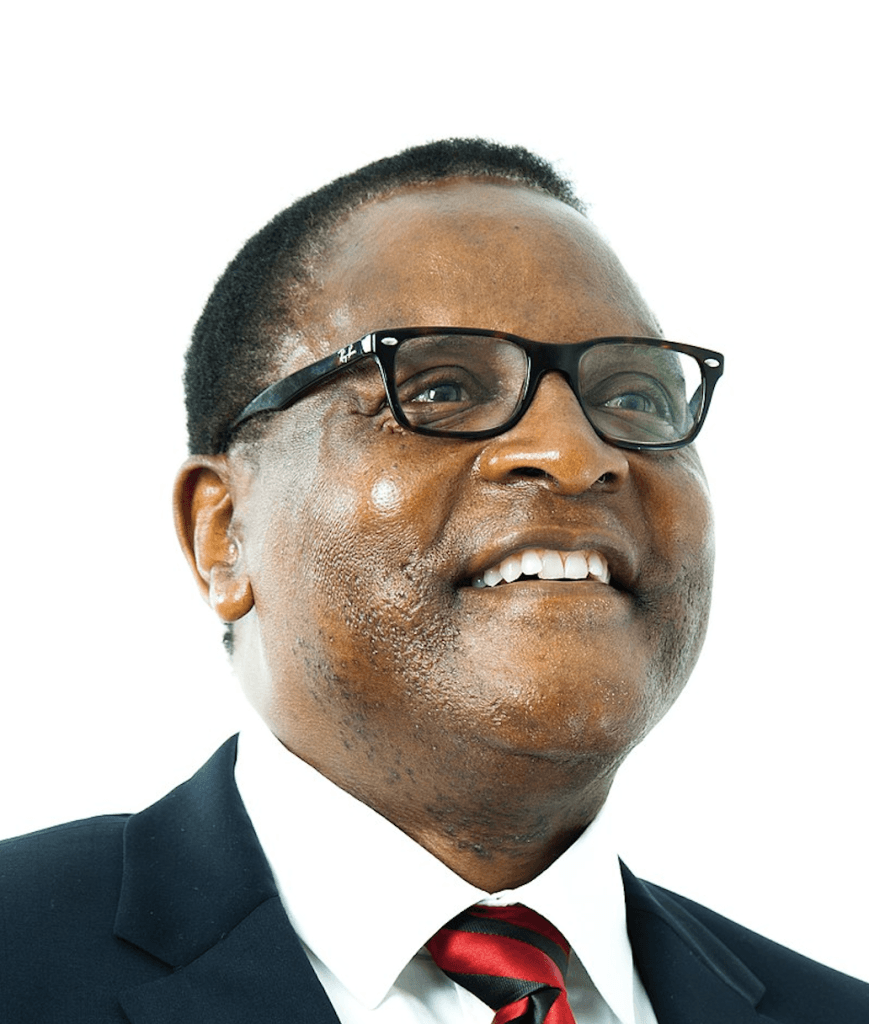

President Lazarus Chakwera, seeking a second term, faces mounting pressure amid an economic crisis, widespread frustration over corruption, and a determined opposition led by 85-year-old former president Peter Mutharika. Opinion surveys suggest the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) holds a consistent lead, raising the possibility of a first-round victory.

A Continental Pattern

Across Africa last year, citizens punished ruling elites for economic hardship, corruption, and broken promises. Ghana’s ruling New Patriotic Party suffered a historic defeat under similar conditions. Now, with inflation in Malawi at nearly 30%, fuel shortages, and food insecurity, many Malawians appear poised to follow the same path.

Chakwera, who came to power in 2020 on promises of prosperity and job creation, now risks being viewed as the very establishment he once challenged. His defenders blame external shocks – the Russia-Ukraine war, climate disasters such as Cyclone Freddy, and prolonged droughts – but voters seem unconvinced.

Limited Choices, Familiar Faces

While 17 candidates are technically in the race, the contest is widely seen as a two-horse battle between Chakwera’s Malawi Congress Party (MCP) and Mutharika’s DPP. For many citizens, this offers little renewal. Mutharika, once rejected by voters, still carries the baggage of corruption allegations and electoral irregularities from his previous tenure.

The sense of a “choiceless democracy” has dampened enthusiasm, even as discontent with the current administration deepens.

Institutions Under Pressure

Perhaps the most important test will be whether Malawi’s institutions – courts, electoral commission, civil society, and the military – can once again manage a high-stakes transition. In 2019, the Constitutional Court annulled the presidential election, citing massive irregularities, and ordered a fresh poll that brought Chakwera to power. The ruling was hailed across Africa as a landmark for judicial independence.

Since then, however, confidence in institutions has wavered. Civil society remains vocal but divided, while skepticism persists over international observer missions, whose assessments in 2019 clashed with the judiciary’s findings.

The possibility of a runoff adds further strain. Malawi’s legal requirement for a candidate to win 50% plus one of the vote makes coalitions essential, but also increases the likelihood of disputes.

Regional and Global Stakes

What happens in Malawi will resonate across the continent. If institutions manage a peaceful transfer of power once again, it would reinforce Africa’s fragile but growing reputation for democratic resilience. A disputed process, however, could add to the instability already plaguing the region.

With just weeks before polls open, the choice before Malawians appears less about personalities and more about whether their institutions can deliver a credible outcome in the face of political tension, economic hardship, and widespread skepticism.