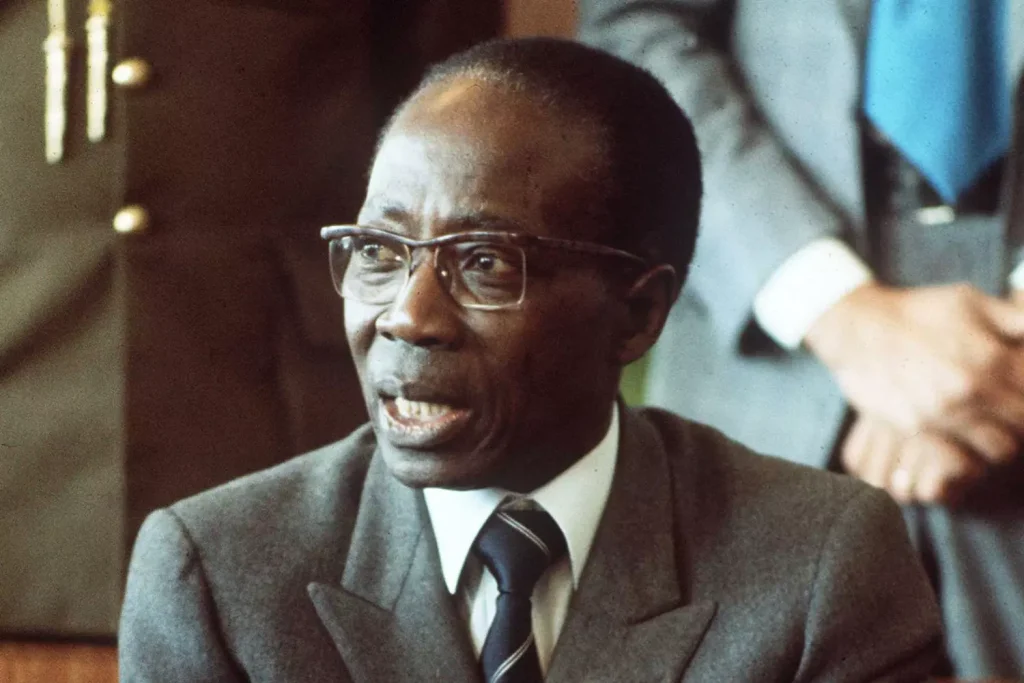

Léopold Sédar Senghor, one of Africa’s most revered intellectuals and statesmen, remains a towering figure in Senegal’s history and the broader Pan-African movement. Born on October 9, 1906, in Joal, a coastal village in Senegal, Senghor rose to become the nation’s first president (1960–1980), a pioneering poet of the Négritude movement, and a global advocate for African cultural identity. His legacy endures as a blend of political leadership, philosophical innovation, and literary brilliance.

Early Life and Education

Senghor was born into a wealthy Serer family with ancestral ties to Senegal’s pre-colonial aristocracy. At age eight, he began his education at a Catholic boarding school, where he initially considered priesthood before pivoting to secular studies. His academic prowess earned him a scholarship to France in 1928, where he attended the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris and later graduated from the Sorbonne with a degree in French grammar in 1935. Though he aspired to study at the École Normale Supérieure, he instead forged a path as a teacher and linguist, laying the groundwork for his future as a bridge between African and European intellectual traditions.

The Négritude Movement: Reclaiming African Identity

During his time in Paris, Senghor co-founded the Négritude movement alongside Martiniquais poet Aimé Césaire and French Guianan writer Léon Damas. This cultural and philosophical movement sought to dismantle colonial narratives by celebrating African heritage, spirituality, and identity. Senghor’s poetry, including works like Chants d’Ombre (1945) and Éthiopiques (1956), became cornerstones of African literature, blending French formalism with Senegalese oral traditions. His famous line, “Emotion is African, reason is Hellenic,” encapsulated his vision of a world where African contributions were central to global culture.

Political Ascendance and Presidency

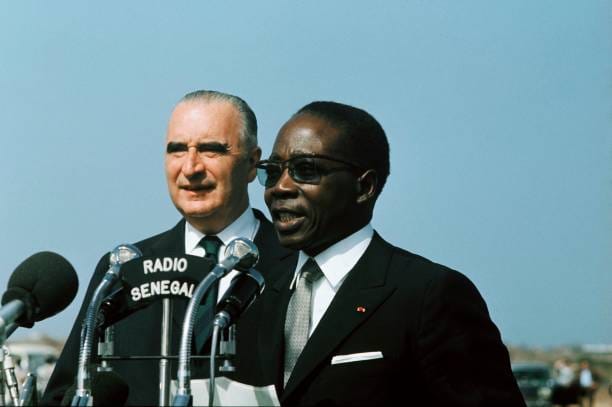

Senghor’s political career began after World War II when he was elected to represent Senegal in the French National Assembly (1945–1958). A pragmatic federalist, he initially advocated for African territories to remain within a reformed French Union, balancing autonomy with cooperation. However, as anti-colonial movements surged, he shifted toward independence, negotiating Senegal’s peaceful separation from the Mali Federation in 1960 to become its first president.

His 20-year presidency was marked by a unique blend of African socialism and cultural revival. Senghor prioritized education, infrastructure, and agricultural development while maintaining close ties with France. Though criticized for his one-party rule, he avoided the authoritarian excesses of many post-colonial leaders. In 1962, he famously clashed with Prime Minister Mamadou Dia, who was imprisoned after an alleged coup attempt. Senghor later introduced limited political reforms, including multi-party elections in 1976.

In a rare act of statesmanship, he voluntarily retired in 1980, handing power to his handpicked successor, Abdou Diouf. “A man knows when it is time to leave the stage,” he remarked, setting a precedent for peaceful transitions in Africa.

Global Statesman and Cultural Ambassador

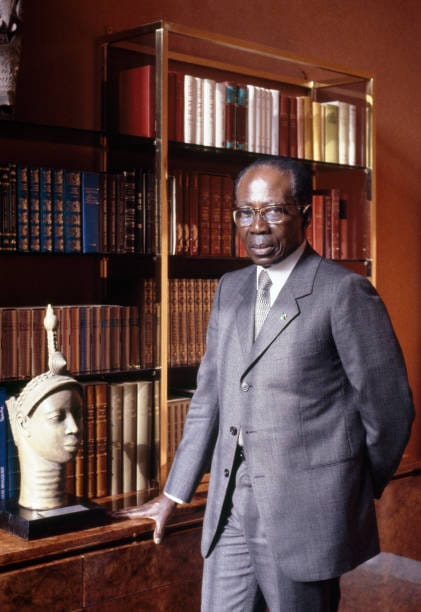

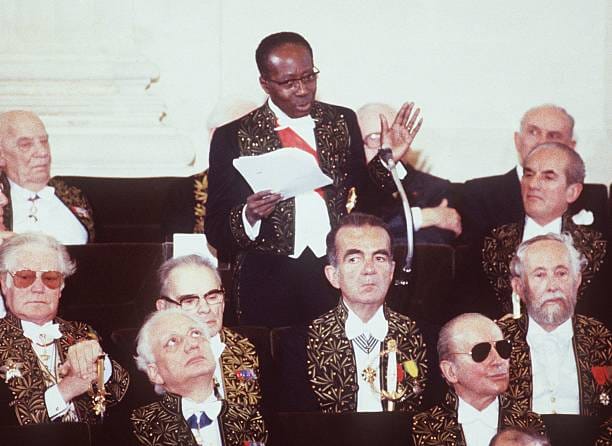

Beyond politics, Senghor championed international dialogue. He was a driving force behind the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), promoting French as a lingua franca for African unity. In 1983, he became the first African elected to the Académie française, France’s most esteemed literary institution—a testament to his dual identity as a Senegalese patriot and a global thinker.

His honors included France’s Grand Cross of the Légion d’Honneur, Spain’s Order of Isabella the Catholic (1978), and a commemorative medal from Iran during the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire (1971). Universities worldwide awarded him honorary doctorates, though his greatest pride lay in Senegal’s cultural resurgence.

Personal Life and Death

Senghor married twice: first to Ginette Éboué, daughter of French colonial administrator Félix Éboué, with whom he had two sons; and later to Colette Hubert, a Frenchwoman who became Senegal’s First Lady. He spent his final years in Normandy, France, passing away on December 20, 2001, at 95. His state funeral in Dakar drew thousands, though the absence of French President Jacques Chirac—attributed to scheduling conflicts—sparked brief diplomatic tensions.

Legacy: The Poet-President

Senghor’s legacy is multifaceted. To critics, his Francophile leanings and elitist governance clashed with grassroots African realities. Yet his vision of Négritude reshaped post-colonial identity, inspiring generations to embrace their heritage unapologetically. His poetry remains a staple in African schools, and his political philosophy of “dialogue between civilizations” still informs Senegal’s ethos of tolerance.

As Senegal continues to navigate modernity and tradition, Senghor’s words resonate: “We must learn to live together, with our differences, in peace.” In a world grappling with cultural erasure and division, his life stands as a testament to the power of identity, intellect, and graceful leadership.