Despite government security escorts known as Agro Rangers, violence remains a daily threat for those struggling to grow crops amid the conflict.

In Dalwa village near Maiduguri, groups of displaced men and women are bused each morning to guarded farmlands surrounded by military trenches. “There is fear — we fear for our souls,” said 50-year-old farmer Aisha Isa, who fled her home more than a decade ago. She continues farming maize and beans to feed her family but admits she only feels partly safe under armed watch.

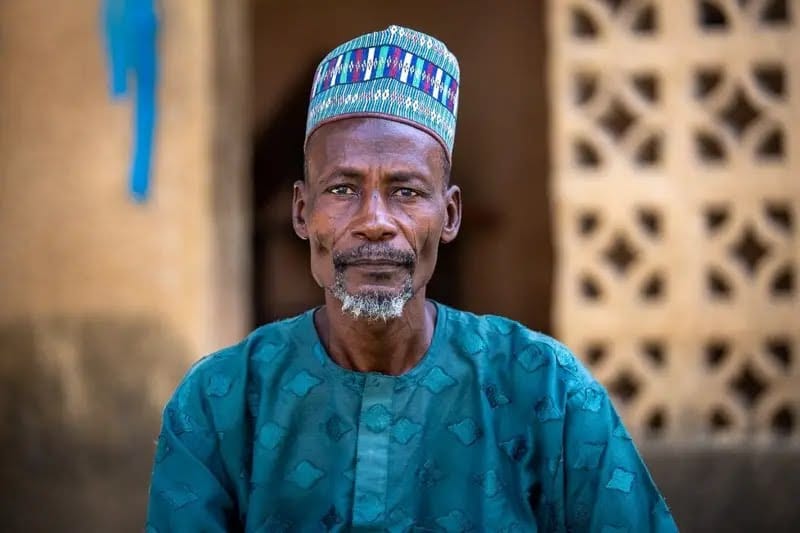

Fellow farmer Mustapha Musa, a father of ten, says he left his home in Konduga years ago. “Some people are kidnapped, others are killed,” he explained. “We can’t go without security.”

According to data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) project, the number of targeted killings of farmers in northeastern Nigeria has more than doubled since 2024. Aid agencies warn that about four million people face food insecurity across the region.

While the Borno State government is pushing displaced people to return to farming as part of its stabilization plan, critics—including the International Crisis Group—say the policy has exposed civilians to greater risk. Militants often extort farmers or demand “taxes” to fund their operations.

Former hostage Abba Mustapha Muhammed described being kidnapped along with nine others. “They killed one man because his family couldn’t pay ransom on time,” he recalled. “We were kept in the forest with no clean water or food.”

The commander of the Agro Rangers, Mohammed Hassan Agalama, insists the security force is helping deter attacks. “When we are on the ground, the terrorists stay away,” he said. However, with only 600 personnel covering vast farmland, their protection is limited.

Farmers’ leaders say fear dominates daily life. Adam Goni, head of the National Association of Sorghum Producers in Borno, said many are too scared to harvest. “My neighbor was killed on his farm. We are angry and frustrated. If the government was serious, Boko Haram would end in a month.”

Despite military claims of progress, communities across Borno say the insurgency—now in its 16th year—continues to destroy livelihoods and deepen hunger. As one farmer put it: “Even if food is scarce, we can’t go to our farms. If we try, they kill us.”