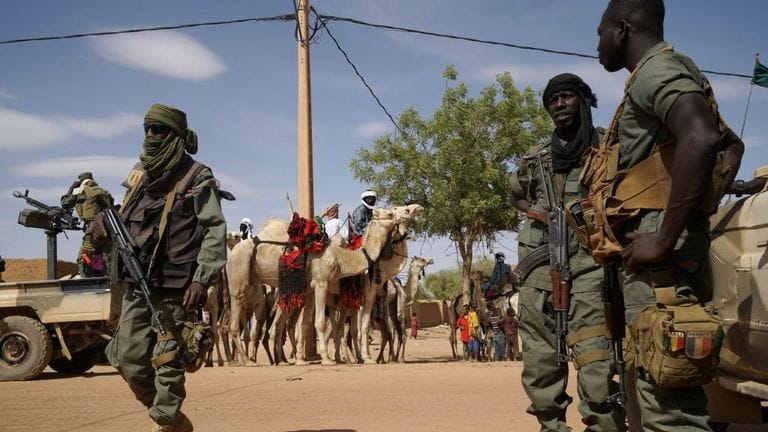

A rebel coalition aligned with al-Qaeda has eclipsed every other armed faction in the central Sahel, fuelling the deadliest twelve-month period the region has recorded since militants violence first spilled out of northern Mali a decade ago.

Jamaʿat Nusrat al-Islām wal-Muslimīn (JNIM) – an umbrella group created in 2017 from five long-standing militant organisations – now operates in all of Mali and in 11 of Burkina Faso’s 13 administrative regions. Field researchers and open-source monitoring units say the movement has also pushed south-ward into northern Benin and Togo and mounted sporadic raids inside Ivory Coast.

280 claimed attacks in Burkina Faso this year

From January to June 2025, JNIM publicised more than 280 operations in Burkina Faso, twice as many as it announced over the same period last year. Independent verification by conflict-mapping NGOs suggests the group has killed nearly 1,000 combatants and local militia members across the tri-border zone in three months, the majority in Burkina Faso’s Nord, Sahel and Est regions.

The violence is mirrored in Mali, where coordinated assaults on 1 July struck seven army positions stretching as far west as Nioro-du-Sahel, within 60 km of the Senegalese frontier. In neighbouring Niger, the militants have resumed highway ambushes around Téra and Torodi, apparently undeterred by the country’s new security pact with Burkina Faso and Mali.

Leadership, recruitment and finance

JNIM is headed by veteran Tuareg commander Iyad Ag Ghali, with Fulani preacher Amadou Koufa acting as deputy. Analysts credit the pair with forging a loose federal structure: local katibas (battalions) enjoy autonomy while strategic guidance flows from a central shura. Most rank-and-file fighters are young men – and increasingly boys – drawn by a mix of ideology, personal grievance and the promise of income in a region where formal employment is scarce.

Funding streams are diverse. Recent fieldwork by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime estimates the movement netted around US $770,000 in 2024 from cattle rustling in a single Malian district; similar schemes operate in Burkina Faso and Niger. Gold mining levies, roadblock “taxes” and protection payments from hauliers supplement revenues. Western hostages, once a lucrative source of ransom, have become rarer as foreigners avoid the interior.

Digital connectivity

Security consultants say militants increasingly smuggle satellite internet kits — including Starlink terminals — along smuggling corridors from coastal West Africa. The equipment gives commanders broadband-level connectivity in remote scrubland, improving real-time intelligence sharing and facilitating encrypted transfers of money.

Regional responses falter

Military takeovers in Mali (2020, 2021), Burkina Faso (2022) and Niger (2023) were all justified as necessary to crush jihadists. Yet casualty data compiled by humanitarian agencies show attacks have accelerated under the new regimes despite waves of army conscription and the arrival of foreign contractors from Russia’s Africa Corps.

Joint Sahel task-forces have withered: all three states have exited the G5 Sahel, while the French counter-terrorism mission “Barkhane” and the UN’s MINUSMA peacekeepers have departed Mali entirely. Human-rights researchers say security forces and allied village militias now face allegations of communal reprisals, reinforcing the narrative JNIM uses to recruit among marginalised Fulani herders.

Outlook

With state authority hollowed out and rival Islamic State cells still active farther east, diplomats fear JNIM’s model – a hybrid of insurgency, local arbitration and taxation – could entrench a de facto parallel administration across swathes of the Sahel. Unless governments couple military pressure with negotiated exit ramps for fighters and tangible civil services for communities, observers warn the movement is poised to deepen its reach south toward coastal West Africa in the year ahead.