Thirty-two years after achieving its long-sought independence, Eritrea finds itself at a crossroads. Once hailed as a beacon of self-determination and resilience, the country today stands burdened by the weight of unfulfilled promises, prolonged militarisation, and limited political reforms.

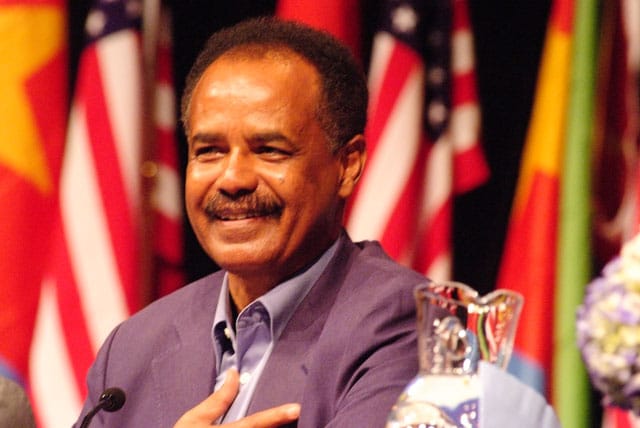

President Isaias Afwerki, who led the liberation struggle against Ethiopian occupation, has remained at the helm since 1993. In the early years, his leadership inspired hope not just within Eritrea but across the African continent. His vision of building a sovereign nation free from foreign interference resonated with many who had experienced colonialism and external domination.

The drafting and ratification of Eritrea’s first constitution in 1997 was initially welcomed as a major step towards democracy. However, the outbreak of war with Ethiopia in 1998 disrupted the country’s political trajectory. Many domestic and international observers believe that the conflict, though real in its causes and consequences, also served to halt planned elections and democratic reforms.

In subsequent years, Eritrea took a unique path—prioritising national unity, self-reliance, and sovereignty over Western-style multiparty democracy. While this approach earned the country criticism from human rights organisations and foreign governments, some Eritreans argue it shielded the nation from the chaos seen in post-liberalisation transitions elsewhere on the continent.

Despite this, domestic frustrations have grown. Eritrea remains under a national service system that, while once seen as a pillar of nation-building, has over time drawn criticism for its open-ended duration and socio-economic toll. The country’s youth, many of whom were born after independence, increasingly seek opportunities abroad.

Within the ruling party and state institutions, critics who pushed for reform—most notably the so-called G-15—were sidelined or detained, leading to a concentration of decision-making in the presidency. Regular cabinet or parliamentary sessions have not been publicly recorded in recent years, and institutions that once promised gradual transformation now appear dormant.

Economically, Eritrea has pursued a policy of minimal foreign aid and cautious development, rooted in a philosophy of independence and national pride. While this has helped preserve policy autonomy, it has also limited access to global markets, investments, and humanitarian assistance during critical periods. The country’s rural and urban infrastructure remains underdeveloped, and economic mobility is constrained, especially for the youth.

Internationally, Eritrea has turned to non-Western partners in recent years, seeking mutual respect and cooperation rather than donor-driven agendas. Strategic engagement with countries like China, Russia, and Gulf states signals a shift in the country’s geopolitical orientation.

Still, many Eritreans continue to call for tangible progress: implementation of a constitution, accountable governance, transparent institutions, and a pathway toward a peaceful political transition. Some believe President Isaias, now nearing 80, could pave the way for such change by addressing these issues directly, while others worry about the absence of a clear succession plan.

There is also a growing diaspora community advocating for reform from abroad, although their relationship with domestic politics remains complex. Within Eritrea, loyalty to the legacy of the liberation struggle remains strong, especially among older generations and within the military establishment.

The road ahead is uncertain. Eritrea is a nation shaped by sacrifice, survival, and pride. As its people mark over three decades of independence, the central question remains: can the ideals that fuelled the liberation war now be reimagined to meet the demands of a new era?

For many Eritreans—at home and abroad—the hope is not just for change, but for a transformation rooted in dignity, unity, and African agency.