Jomo Kenyatta was born as Kamau wa Ngengi around 1897 in Gatundu, British East Africa (modern-day Kenya). After the death of his parents, he was raised by his uncle. As a young man, Kenyatta moved to Nairobi, where he worked in various jobs, including as a clerk and water-meter reader for the Nairobi City Council.

His early exposure to European settlers, colonial administrators, and Christian missionaries influenced his worldview. He eventually converted to Christianity and adopted the name “Johnstone Kamau,” later changing it to Jomo Kenyatta — “Jomo” meaning “burning spear” and “Kenyatta” referring to the beaded belt he often wore.

“When the roots of a tree begin to decay, it spreads death to the branches.”

A metaphor that framed his later arguments against colonial corruption of African traditions.

In the 1920s, he became involved with the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), advocating for Kikuyu land rights and against colonial injustices. Recognizing the need for broader education, Kenyatta traveled to London in 1929 as the KCA’s representative.

Life Abroad and Political Formation

Kenyatta went to Britain in 1929 to represent Kikuyu land grievances. During his long stay (1929–1946), he studied at various institutions, including the London School of Economics, where he was influenced by anti-colonial thinkers, under the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski.

While abroad, Kenyatta sharpened his advocacy for African self-rule and cultural pride. He published his famous book, “Facing Mount Kenya” (1938), an anthropological study defending Kikuyu traditions against colonial misrepresentation. He also attended the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945 alongside figures like Kwame Nkrumah, emphasizing African unity and decolonization. His famous line captured his stance:

“Our children may learn about heroes of the past. Our task is to make ourselves the architects of the future.”

Return to Kenya and the Road to Independence

Kenyatta returned to Kenya in 1946 and soon became a leading figure in the growing nationalist movement. He joined the Kenya African Union (KAU) and became its president in 1947. Under Kenyatta’s leadership, KAU pushed for African political representation, land reforms, and an end to colonial rule.

However, tensions escalated with the outbreak of the Mau Mau Rebellion (1952–1960), a violent uprising mainly by the Kikuyu people against colonial authorities. Though Kenyatta denied involvement, British authorities arrested him in 1952, portraying him as the “leader to darkness and death.” He was convicted and imprisoned during the infamous Kapenguria Trial, spending almost nine years either in jail or under restrictive house arrest.

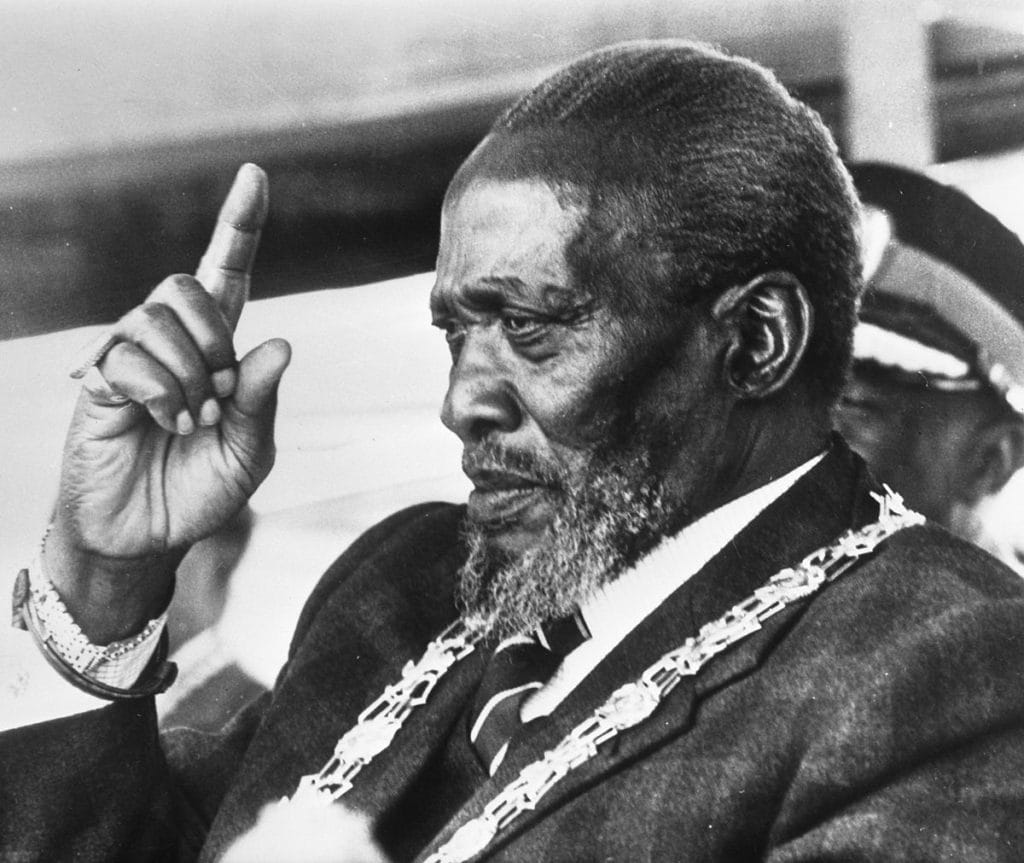

Leadership and Presidency (1963–1978)

Following his release in 1961, Kenyatta led Kenya to independence. He became the president of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and led negotiations with the British for Kenya’s independence. Kenya gained internal self-government in 1963, with Kenyatta as Prime Minister, and full independence on December 12, 1963. A year later, Kenya became a republic, and Kenyatta became the country’s first President. He sought national unity under the call of “Harambee” — meaning “pulling together.” He often reminded Kenyans:

“Unity cannot be taken for granted. It must be maintained and protected.”

His rule focused on several key areas:

- Nation Building:

Kenyatta worked hard to foster a national identity, avoiding ethnic fragmentation that plagued many new African states.

“We do not want to fight. We want peace in which we can build our country.”

- Economic Development:

His government emphasized capitalist-oriented economic policies, encouraging foreign investment and protecting private property. Agricultural production, especially cash crops like coffee and tea, expanded. - Land Redistribution:

Kenyatta initiated land resettlement schemes to address the colonial legacy of land dispossession. Yet much of the best land ended up with political loyalists rather than the poor majority. Still, his broader vision remained:

“The land is ours. It is not inherited from our ancestors but borrowed from our children.”

- Political Stability and Centralization:

Kenyatta steered Kenya toward a de facto one-party state. Political dissent was often suppressed, and opposition leaders were sometimes harassed or marginalized. For example, the assassination of Pio Gama Pinto (1965) and Tom Mboya (1969), both prominent politicians, raised suspicions of state involvement, though never conclusively proven. - Foreign Policy:

Kenyatta maintained a moderate, pro-Western foreign policy, aligning Kenya with Britain and the United States during the Cold War. He avoided the radical socialist path taken by some other African nations. - Consolidation of Power:

Over time, Kenyatta’s leadership grew more authoritarian. Loyalty to the president became a requirement for political survival. His rule was also marked by growing nepotism and favoritism toward his own Kikuyu ethnic group.

Jomo Kenyatta’s Legacy

Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, while still in office. He left a complicated legacy:

- He is revered as the “Father of the Nation” who led Kenya to independence and laid the foundations for national unity and economic growth.

- However, he is also criticized for authoritarian tendencies, ethnic favoritism, and the entrenchment of economic inequality.

One of his most profound reflections near the end of his life was:

“Leadership is a privilege to better the lives of others. It is not an opportunity to satisfy personal greed.”

His vision, charisma, and pragmatism remain influential in Kenya’s political and cultural life. His son, Uhuru Kenyatta, would later follow in his footsteps to become Kenya’s fourth president (2013–2022).